There are so many applications how this, funny but well explained, video applies to how we learn music. Watch the video first, then read the analogies below.

"Learning a bicycle is a life skill, one that the brain never forgets." The musical application of this is how we practise and the importance that we practise "correctly". While in university, a friend commented how a student will learn a passage inaccurately, then spend the next 7 months correcting that mistake, to only play it wrong at the time of performance. Over the last three decades of teaching my friend’s comment has come to me many times. I have found her statement to be very true. Over the years I have explained to students about neural pathways and how we learn. A good example is to get a pencil and draw a squiggly line, which represents the neural pathway of the first time something is learned. Trace over the same line 10 times, following the first line, which represents the practising of that passage we just learned. What students will see is how the line becomes thicker, more permanent. After the tenth time, draw a deviation to the line (which is the "correct" way to play a passage). They soon see the comparison of how thick the "wrong" way is compared to the "correct" way. If they slip and do the wrong way they are only strengthening that path. So it takes many times of doing it correctly and never playing it the wrong way, before the brain prunes (removes) the old way of playing that passage. However, when under pressure, and if the first (incorrect) neural pathway has not been pruned from our brain, most times, students will play the wrong way – the brain will revert to the first impression of the path because it is the strongest. They say you need to repeat something 27 times in a row correctly to cancel out the ONE time you did it incorrectly. If a student plays a passage 2 times incorrectly, they now need to repeat it 54 times in a row to cancel out those two times. If a student gets to number 52, and plays it wrong again, they now need to play it 81 times in a row correctly to cancel out the 3 times they played in incorrectly. Learning a piece of music is like learning to ride the bicycle – “the brain never forgets”. As Destin stated in the video, after he could ride the backward bicycle, “It was weird though, it’s like there’s this trail in my brain, but if I wasn’t paying close enough attention to it, my brain would easily lose that neural path and jump back onto the old road it was more familiar with.” The old adage “you need to make a good first impression” is very true when it comes to learning a new piece of music or skill.

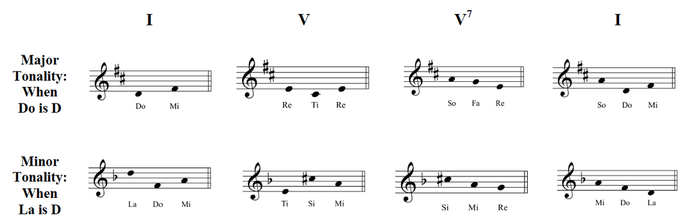

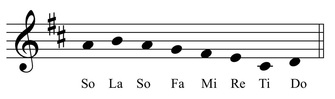

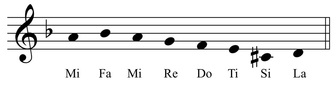

"Knowledge does not equal Understanding" (around the 1:20 minute mark). This has many references to how we learn and process music, so I will pick one reference – “understanding”. Many times in our teaching we give knowledge to students, but do we really give them the "understanding" of music, one of the key principles of Music Learning Theory. Edwin E Gordon defined audiation as "Hearing and comprehending in one's mind sound of music not, or may never have been, physically present. It is not imitation or memorization" (Gordon, 2012, p. 389). There are six stages and eight types of audiation (more on this in future blog posts). Suffice it to say, for students to understand music, they need to "hear", "experience", and "feel" music. With some students they "hear" and "feel" that the next chord that is to be played is the dominant, or the subdominant, or that it moves back to the tonic. And they understand that they are playing: tonic, dominant, subdominant; playing in a major or minor key, and; they “feel” that they are playing in duple, triple, or an unusual metre. It is when we guide students in their learning of music (rather than teaching them knowledge) that students play with understanding, improvise, experience music, and reach their highest level of music aptitude.

"Brain Plasticity. Children's brains have a higher rate of plasticity than adults". Brain plasticity refers to how the brain changes, the creation of new neural pathways, the pruning of unused neural pathways. Around the 4-minute mark in the video, Destin comments how his 5- to 6-year-old son “In two weeks he did something that took me 8 months to do, which demonstrates that a child has more neural plasticity. It’s clear from this experiment that children have a much more plastic brain than adults. That’s why the best time to learn a language is when you’re a young child.” This is very true with children, but does not apply only to language. A person’s music aptitude is the highest at the time of birth and can change widely during the first years of life, with the earliest years being the most sensitive for learning music. Before music aptitude stabilizes around age nine, it is ever changing and develops in association with environmental influences. (The stabilization of music aptitude coincides with the maturation of the myelination of the brain, which occurs around age 10 to 12.) Neuroscience researchers have found that there is a critical period and sensitive period for learning music, supporting Dr. Gordon’s statement, “The critical age for guidance in music is from birth to eighteen months of age. The sensitive age is sustained until approximately five years old. Children learn more during the critical stage than any other period of life” (Gordon, 2012, p. 47).

In a literature review I just completed, it was hypothesized that connections could be made between the field of neuroscience, Gordon’s early theories, and principles of Music Learning Theory (MLT). The purpose of the literature review was to investigate how neuroscience research lends support to how infants learn and process pitch and rhythm. The following questions were explored in the literature review:

1. What auditory cortical processing is evident in children and infants learning pitch?

2. What auditory cortical processing is evident in children and infants learning rhythm?

The hypothesis that principles of MLT are supported with research in neuroscience was sustained. In Table 1, the similarities between findings in neuroscience research and practical applications of MLT are illustrated (with the respected studies reviewed).

Table 1.

Neuroscience Findings and Practical Applications to Principles of Music Learning Theory

Element Timbre | Neuroscience Finding From 4-months-old to 6-years-old a preference to timbre can be developed (Fujioka et al., 2006; Shahin et al., 2004; Trainor et al., 2011). | Practical Application to MLTExposure to different timbres and instruments. |

Pitch | Four-month-olds can distinguish pitch, as harmonic relations are merged into a single percept indicating a major shift in how pitch is represented between 3- to 4-months of age (He and Trainor, 2009). | Sing songs in the same keyality each time it is sung. |

Familiarity | Infants develop pitch representation preferences to particular timbre, which suggests that infants as young as 4-months-old can reflect learning (Trainor et al., 2011). | Sing the same songs 4 to 6 times over a short period of classes. |

Harmony | Six-month-old infants are capable of segregating mistuned components of a harmonic frequency suggesting they use harmonicity cues to distinguish simultaneous sounds (Folland et al., 2012). | Sing songs in various modalities and keyalities. |

Metre | As early as 2-months-old infants show a preference to unusual metre through novelty preference (Gerry et al., 2010; Hannon and Trehub, 2005a.b; Trainor et al. 2009). | Singing of folksongs in usual and unusual metres. |

Rhythm | Twelve-month-olds, with no prior exposure, are capable of distinguishing rhythmic variations in foreign folk music (Hannon & Trehub, 2005b). | Use of rhythm chants in varying metres. |

Movement | Infants learn metre and rhythm through physical movement (Gerry et al., 2010; Hannon and Trehub, 2005a.b; Trainor et al. 2009). | Movement and activities incorporated into songs and rhythm chants. |

Enculturation | Shortly after birth rhythm perception develops in infants in regard to culture-specific biases, before stabilizing around 1-years-old (Gerry et al., 2010; Hannon and Trehub, 2005a.b; Trainor et al. 2009). | Acculturation: Use of folksongs in various keyalities, modalities, and metres. |

Brain Plasticity | Plasticity and normal maturation of the brain is developed by a year of musical training in children aged 4 – 6 years (Fujioka et al., 2006; Shahin et al., 2004). | Leaving Preparatory Audiation Stage and entering Audiation Stage – informal to formal guidance. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed