This is a sneak peak of an interview/article that will be coming out in the January 2016 issue of OPUS. This is an interview conducted with myself and with Soo Jin Chung, a student at the University of Toronto. I felt she had very good questions for the interview in regard to specific things from the articles that were previously published in OPUS. This is the last of the the four-article series.

Soo Jin Chung is currently enrolled in her third year of Bachelor of Music degree in piano performance at the University of Toronto. In her short career, she has been awarded numerous scholarships including a full tuition for her four-year program. She is now studying under the tutelage of renowned pianist James Parker. Chung regularly performs solo and chamber music, and has recently appeared as the guest soloist with the Mississauga Symphony Orchestra and Toronto Sinfonietta.

During the fall term of 2015, the Career Project of Teaching Methods - Piano (PMU260Y1) at the Faculty of Music, University of Toronto, examines a variety of professions related to music performance and education in our current society. While receiving intensive training in music, the goal of this project is also to inform students of the complexity of music professions in 21st century Canada. As part of the course requirement, Soo Jin Chung interviewed Gregory Chase with the questions related directly to his previous articles published in OPUS. The following are excerpts from that interview.

SJC: In your article, “Developing the Internal Rhythm within our Students,” that appeared in the Fall 2015 issue of OPUS, you are essentially introducing a new component to learning and analyzing rhythms to students by approaching them with appropriate syllables and putting them in context to the meters.

GC: I guess I would first mention, that I want to give credit where credit is due, and that is, that I personally am not introducing a new component to learning and analyzing rhythms, but rather this is from the work of Edwin E. Gordon, a great music educator and music psychologist in the United States. He began this work in the 1960s so it has been around for over half a century. However in saying that, this is a relatively new approach for us here in Canada though.

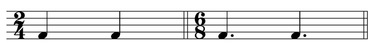

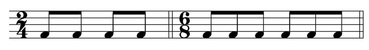

The concept of adding appropriate syllables and putting the syllables in context to meters is not a new concept, once we think about it; as we often teach theory this way, by indicating the beat function. An example of this is when we talk about duple meter we indicate that beat one is strong and beat two is weak. Or in quadruple meter we say beat 1 is strong, beat 2 is weak, beat 3 is medium, and beat 4 is weak. Or in triple meter, we say, beat 1 is strong, beat 2 is weak and beat 3 is weak. By assigning specific rhythm syllables to the beat function, we are indicating what is the function of the beat within the measure, rather than what is the arithmetic breakdown of the rhythmic value of the individual notes. The former yields a more musical approach, while the latter is a mathematical approach.

SJC: While this has proven to aid the students in recognizing the meters of music, how will this guide the students later on to read, recognize, and understand the numerical values behind the notes and rests that make up the rhythm?

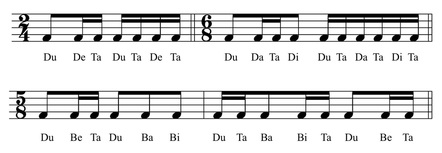

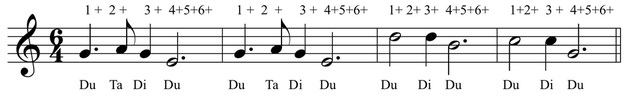

GC: I think often we get caught up that a quarter note gets 1 beat, and a half note gets 2 beats and an eighth note gets half a beat, and so on. I think we fall into the trap of teaching individual rhythmic values rather than teaching the rhythmic passage as a whole. What happens is we take context completely out of the picture and deal with the individual content. For example, if I just say “t”, it means nothing. We know it’s a letter of the alphabet, but that is about it. There isn’t any context. If I clap an eighth note, it means nothing to us, as there is no context – it’s an eighth note and that’s it. However if I say the word “rabbit”, now the “t” appears in context of other letters but then we often ask, “okay, so what about the rabbit?” Now if I clap two-eighth notes followed by a quarter note, I have indicated how that eight note fits in the context of the notes around it, but it still doesn’t tell us what meter we’re in, where does this fit within the overall rhythmic passage, is this at the beginning, middle, or end of the measure, or is it going across the barline etc.? So if I clap that pattern, we really don’t know, is the first eighth on the strong beat, the weak beat, the medium beat, are we in duple meter, triple meter, or irregular meter? So there are loads of unknown variables of how to interpret that pattern, and how to play it in the overall musical context in which it appears. Now going back to the word “rabbit”. If I put the word “rabbit” within the context of the sentence, “I saw a rabbit running across the park”, now it makes sense; as we have the full context of the word “t”. Just as if I chant the two-eighth and quarter note pattern as “Du-ta De”. You now have the following information:

By using a numerical (arithmetic) counting system we really don’t get this same information, unless it’s all outlined as I have done with the bullets, so there is a lot of explaining that has to happen with the student when we use the numerical approach. In the first example we would count “1+ 2”. That doesn’t tell us the meter at all, as we have no indication of what comes next, e.g. are there 3 beats in the measure, are there 4, 6, etc? In the second example this will tell me a bit more if I count, “3 + 1”. As then we know, oh, we’re going over a barline because we heard “1”. But lets move this pattern to the beginning of the measure, again if we count “1 + 2”. We really have no idea of any meter, how many beats in a measure and so on. So it’s very inconsistent, whereas, by using rhythm syllables we know exactly what meter we are in, and where we are in the measure in relation to beat function. So it provides loads of information with just three syllables. It provides the syntax of that rhythm pattern.

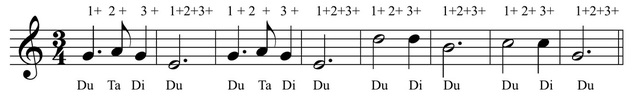

Here is where the confusion arises in an arithmetic approach to counting. In 4/4 a quarter note gets 1 beat/count. In 2/2 though, a quarter note gets half a beat/count. In 2/8 a quarter note gets two counts. So it changes dependent on the meter. This causes a lot of confusion for students. Whereas, if we count in regard to beat function we are always thinking in regard to macrobeat (the big beat) and the microbeat (the little beat), a more musical approach. As you saw in the article, “Developing the Internal Rhythm within our Students” in the Jan 2015 issue of OPUS, examples of Silent Night using the arithmetic approach to rhythm show there are numerous ways of counting the various meters, which is quite confusing. With beat placement you can count the various meters in the same manner, much easier for students to understand and it makes for a stronger musical interpretation.

Even now, when I teach theory to my students, I’m getting away from the arithmetic approach to rhythm and am basing it on beat function. There is no need to use the arithmetic approach to rhythm, but rather it’s based on macrobeat, microbeat, divisions and elongations. Even in teaching theory where students have to fill in rests or missing beats, this can be done through the understanding of divisions and elongations of the beat. There really isn’t a need to take the arithmetic approach to rhythm, as it’s unstable, because it changes, dependent on the time signature. Rather I take an approach based on what is the macrobeat, what is the microbeat, and deal with enrhythmic values of patterns. Once the macrobeat and microbeat are defined, all else falls into place.

SJC: Is there a point in the training where you make the transition to numerical reasoning?

GC: As mentioned above, no. There isn’t any reason to use numbers with rhythms if using a beat function approach to rhythm. In teaching students theory, I’m amazed how much easier this is for them and they pick it up way faster than when I use to teach rhythm using an arithmetic approach. But again, now I know, this is how the brain learns rhythm, so it’s a more organic approach and is an approach based on how the brain learns and processes rhythm.

SJC: How can teachers guide the students in a way that they fully understand the context instead of simply memorizing and regurgitating the rhythmic syllables?

GC: The secret is start using this from the very beginning, and foremost, the teachers have to change their own thinking. We generally teach the way we were taught, and so it takes some “un-learning” to fully accept this when we’ve all been taught to count using numbers. It’s important for the teacher to fully understand first (as with most things we teach). I approach this first with lots of Aural/Oral associations. We will chant lots of rhythms before students see the notation of these patterns and they will repeat back the rhythm pattern on “bah” or other neutral syllable. As well, at the beginning rhythm patterns, and tonal patterns are taught separately from one another. This way they can concentrate on one thing at a time, again a process of how the brain learns. As we do this, we start building a musical vocabulary for the student, and they have the musical comprehension right from the beginning, of knowing if they are in duple meter, triple meter, the macrobeats, microbeats and so on.

To really give students the context and understanding of rhythm, we use lots of movement. Once they are comfortable with the aural/oral level, then we move to the verbal association level, which is using the rhythm syllables that I mentioned earlier. In both the Aural/Oral and Verbal Association levels, we start with duple meter, and then move to triple meter; and again this is based on how the brain learns and processes rhythm. It’s important to remember that the rhythm syllables do not teach rhythm, (just as a metronome does not help students to play the correct rhythm), rather the rhythm syllables are a tool to help students understand rhythm. That is where to start and then there are a series of sequential levels and activities that follow after this.

SJC: Are there method books or music books for young students in the market that are easily adaptable to your method of teaching rhythm? Do you believe it’s applicable to all music?

GC: There is a piano method series called, “Music Moves for Piano” by Marilyn Lowe. These are published by GIA Publications in Chicago. Here is Marilyn’s website: http://www.musicmovesforpiano.com/

Yes, I do believe this is applicable to all music, and all levels of music. I use this with all my students, even those at the Associate level.

SJC: You suggest similar approaches in your writing, “I don’t teach my students to count, because I want them to feel the beat.” Published in the Fall 2015 issue of OPUS. If you teach the meters and macrobeats/microbeats first to students, how do you propose on making the transition to figuring out rhythms?

GC: Do you mean the rhythmic values of the notes? I guess I’m not sure what you mean by “figuring out rhythms”. First we don’t take a look at individual notes, as that would be similar to only saying one letter at a time when we speak. Rather we take a look at the rhythmic patterns. However, before we begin, we take a look at the Measure signature (time signature) to determine what is the macrobeat and what is the microbeat. Or at the higher levels, we take a look at the context of the passage. Once the macrobeat and microbeat are understood, then we move to the divisions of the macrobeat and microbeat and then to the elongation of the macrobeat and microbeat. It’s part of the sequential process.

SJC: While this may result in more musical growth and understanding, wouldn’t this, in a sense, limit the students’ concepts of “counting” or figuring out rhythms to only the meters they know?

GC: Hmmmmm . . . I would say the opposite. That is what I love about a beat function approach to rhythm, is that it gives more flexibility in understanding the various meters. Where as with an arithmetic approach to counting the student needs to understand the individual rhythmic value of each note. If I say to students we are in duple meter, they know they will be audiating DU DE, or in triple they know they will audiate DU DA DI, and then we have the various rhythm syllables for irregular meters as well. With the arithmetic approach, they have to know whether the quarter note gets 1 count, 2 counts, half a count, two-thirds of a count and so on. So in that sense, the numerical/arithmetic approach is more limiting to only the meters/time signatures that they know.

SJC: I see more and more modern music being incorporated into the repertoire selections of the RCM examinations even for lower levels. If you were to encounter a piece without standard meter, how will you prepare the students to work on that piece within the frames of your usual teaching?

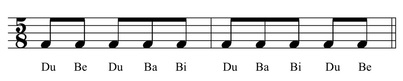

GC: When you mention standard meter, I’m assuming you are referring to duple and triple meter? So with irregular meter, what we (those who base their teaching on the framework of Music Learning Theory, which is the process of how we learn music), we would refer to 5/4, 5/8 etc as Unusual paired meter, and 7/8, 7/4 etc to Unusual Unpaired meter. For unusual paired meter we use the syllables Du Be Du Ba Bi (if grouped 2 and 3), or Du Ba Bi, Du Be (if grouped in 3 and 2). In 7/4, 7/8, etc we would use the syllables, Du Ba Bi Du Be Du Be (if grouped in 3 + 2 + 2), again this would vary according to the groupings. An advantage to this over the numerical accounting to 1 2 3 4 5 or 1 2 3 4 5 6 7, the grouping of the patterns is clearly understood by how it’s counted with the rhythm syllables, which will result in a more musical treatment to rhythm.

SJC: The object to your teaching is to personally adjust and cater to every individual student’s needs. However, just by looking at how you approach rhythms, you seem to have your own firm set of teaching methods. How do you generally balance the specific needs of students to your style of teaching?

GC: Okay, I think this is taken a bit out of context, but I understand what you’re asking. J I think most us do teach to the individual students and to where they are at, one of the beautiful things about teaching private lessons. So in many cases this isn’t new (to teach to the individual differences of the student), but it’s often not mentioned in the teacher’s teaching philosophy. Unlike the school system where the teacher has to teach to the whole class, we get to work with students at the level they are learning. What I mean by that, while Johnny may be at this stage, Susie may be at that stage, and so that guides my instruction. I’m not requiring that all my students learn duple rhythm verbal association this week and they can’t move on until everyone has done this, instead, while one student may be learning duple meter at the aural/oral level, another may be learning it at the verbal association level, while another student may be learning unusual unpaired meter, and so on. What I mean by I teach to the individual differences of the students, is that while one student may be high in rhythm aptitude, but low in tonal aptitude, I work with this accordingly, giving rhythm patterns that are geared to students with high rhythm aptitude and will give tonal patterns that are geared towards those with lower tonal aptitude. So not all students will get the same patterns, nor in the same order, nor learn at the same pace. I follow their guidance and learning level rather than saying that we must get through a unit in the method book every two weeks, or after this piece, lets turn the page and you must do that piece. So the instruction really varies from student to student, but the techniques used in delivering the concepts are pretty much the same. Now I even say that with hesitation because again there are even variances in that, due to the individual student.

SJC: How does this apply to transfer students?

GC: You present a very good question in regard to how it applies to transfer students. This is quite an untraditional approach, although very sound in neuroscience (pardon the pun). So with my transfer students I do carry on with on how they have been taught (symbol/sign before sound). However, I will still work with them at the aural/oral and verbal association levels and work through the sequential process accordingly. So my teaching then becomes compensatory instruction. I use their sight reading and ear training lots to incorporate these new concepts and so that helps to bring them up to where I want them to be overall. It’s a process, and again, that process varies from student to student, depending on where they are at, musically. And I guess that is the key, as I teach to the musical age of the student, not the chronological age of the student.

SJC: You must constantly come across many new things through your research hence discovering the innovative ways to teach rhythm and intervals. What are some difficulties you have as a teacher, mentor, or colleague deriving your own materials away from the popular, common, or traditional methods of teaching?

GC: In regard to “materials” I’m assuming you are talking about physical materials, e.g. books and such? That is the beauty of how I teach, is that it can be used with any kind of music. It’s not indigenous to any one type of music. The framework of Music Learning Theory is used for early childhood music classes, which I teach, any private instrument, elementary music class, high school jazz band, concert band, university music. I guess because this is a framework that I use it’s a matter of adapting it to what I’m teaching. I guess the biggest challenge is finding the time to find the materials to use in incorporating this framework for the specific learning level of each student. So it does mean pulling from various resources if I’m not using the Music Moves for Piano method series. The beauty of this framework is that it can be used with the popular, common, or traditional method books, I just approach the learning of these pieces differently than what is stated. Now I’m selective in what pieces I use with my students, and I often do change them, according to learning level of the student, so it does require a fair bit of digging and prep work.

SJC: Do you feel that teachers should constantly strive to adjust and adapt their teaching in correspondence to newer researches in early education?

GC: Yes, providing it’s proper research. With advances we have in neuroscience we are now able to learn so much more about how our brain learns and processes information. We are finding that often times the traditional way is counterproductive to how we really learn. It’s really only been in the last 15 years where neuroscience has really taken off, with the use of MRIs, CT scans, and so on. And there is still so much we don’t know about the brain and how it works, we’re still very much in the infancy stage of this whole process.

SJC: Is it safe to assume that your teaching focuses heavily on the psychology of the students?

GC: If we are speaking of the psychology of how students learn, then yes, that is a safe assumption to make. J I think the key point to establishing an individualized teaching approach is that one has to understand how we learn and process music. So we need to understand that whole learning process, and this is huge and why I decided to do my masters degree in Music Learning Theory.

SJC: What are some key points to address when establishing individualized teaching methods to any given student?

GC: I think it’s important to realize that each student is at a different musical age. And that is especially true in the birth to 6 year of age. However, we may still get someone who comes to us at age 7 for piano lessons, but they are really at the infant musical age level (acculturation stage), and meanwhile we may get a student who is 5 years of age and has already entered the audiation stages of learning. So by doing various informal activities a person is able to assess their musical age and then you work on from there. The other thing to remember is that although they may be at one stage rhythmically, they may be at a different learning stage tonally, and even at a different learning stage harmonically. However, once the student’s music aptitude has been tested, then of course that gives a more objective approach to the teaching and brings it to another level of individualized instruction.

SJC: You mentioned that learning music is like learning a language. What are some common reverse psychologies that music teachers practice in their teaching?

GC: Well the most common reverse psychologies that music teachers, who use a traditional approach, would be the equivalent of saying to a child that you cannot speak a word until you can read the word. J We know that is crazy, and would say that is crazy thinking, but yet we do it with music all the time - sight/symbol before sound. At least I know I was guilty of doing that for 30 years of teaching. As I mentioned earlier, we usually teach the way we were taught and most of us have been taught to read/decode first. And we miss the most important stage, and that is the stage of listening to music.

SJC: History has shaped teaching music that way it is for decades – so why the change now?

GC: Believe it or not, this is how music was originally taught, way back when. I’m speaking back in Bach’s time. It wasn’t until Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press that this approach changed. Up until that time, music was taught as an “aural” art, rather than a “visual” art. So in many ways it’s not changing but rather going back, or rather, thinking that all things move in a cyclical manner, that we are now returning to the origin of how music was taught, and that is, aurally.

Soo Jin Chung is currently enrolled in her third year of Bachelor of Music degree in piano performance at the University of Toronto. In her short career, she has been awarded numerous scholarships including a full tuition for her four-year program. She is now studying under the tutelage of renowned pianist James Parker. Chung regularly performs solo and chamber music, and has recently appeared as the guest soloist with the Mississauga Symphony Orchestra and Toronto Sinfonietta.

During the fall term of 2015, the Career Project of Teaching Methods - Piano (PMU260Y1) at the Faculty of Music, University of Toronto, examines a variety of professions related to music performance and education in our current society. While receiving intensive training in music, the goal of this project is also to inform students of the complexity of music professions in 21st century Canada. As part of the course requirement, Soo Jin Chung interviewed Gregory Chase with the questions related directly to his previous articles published in OPUS. The following are excerpts from that interview.

SJC: In your article, “Developing the Internal Rhythm within our Students,” that appeared in the Fall 2015 issue of OPUS, you are essentially introducing a new component to learning and analyzing rhythms to students by approaching them with appropriate syllables and putting them in context to the meters.

GC: I guess I would first mention, that I want to give credit where credit is due, and that is, that I personally am not introducing a new component to learning and analyzing rhythms, but rather this is from the work of Edwin E. Gordon, a great music educator and music psychologist in the United States. He began this work in the 1960s so it has been around for over half a century. However in saying that, this is a relatively new approach for us here in Canada though.

The concept of adding appropriate syllables and putting the syllables in context to meters is not a new concept, once we think about it; as we often teach theory this way, by indicating the beat function. An example of this is when we talk about duple meter we indicate that beat one is strong and beat two is weak. Or in quadruple meter we say beat 1 is strong, beat 2 is weak, beat 3 is medium, and beat 4 is weak. Or in triple meter, we say, beat 1 is strong, beat 2 is weak and beat 3 is weak. By assigning specific rhythm syllables to the beat function, we are indicating what is the function of the beat within the measure, rather than what is the arithmetic breakdown of the rhythmic value of the individual notes. The former yields a more musical approach, while the latter is a mathematical approach.

SJC: While this has proven to aid the students in recognizing the meters of music, how will this guide the students later on to read, recognize, and understand the numerical values behind the notes and rests that make up the rhythm?

GC: I think often we get caught up that a quarter note gets 1 beat, and a half note gets 2 beats and an eighth note gets half a beat, and so on. I think we fall into the trap of teaching individual rhythmic values rather than teaching the rhythmic passage as a whole. What happens is we take context completely out of the picture and deal with the individual content. For example, if I just say “t”, it means nothing. We know it’s a letter of the alphabet, but that is about it. There isn’t any context. If I clap an eighth note, it means nothing to us, as there is no context – it’s an eighth note and that’s it. However if I say the word “rabbit”, now the “t” appears in context of other letters but then we often ask, “okay, so what about the rabbit?” Now if I clap two-eighth notes followed by a quarter note, I have indicated how that eight note fits in the context of the notes around it, but it still doesn’t tell us what meter we’re in, where does this fit within the overall rhythmic passage, is this at the beginning, middle, or end of the measure, or is it going across the barline etc.? So if I clap that pattern, we really don’t know, is the first eighth on the strong beat, the weak beat, the medium beat, are we in duple meter, triple meter, or irregular meter? So there are loads of unknown variables of how to interpret that pattern, and how to play it in the overall musical context in which it appears. Now going back to the word “rabbit”. If I put the word “rabbit” within the context of the sentence, “I saw a rabbit running across the park”, now it makes sense; as we have the full context of the word “t”. Just as if I chant the two-eighth and quarter note pattern as “Du-ta De”. You now have the following information:

- I’m in duple meter (rhythm syllables for duple meter are: DU for macrobeats and DE for microbeats – with the “ta” being a division of the macrobeat and microbeat)

- The first eighth note is on the strong/big beat (macrobeat)

- The second eighth note is on the division of the beat

- The quarter note is on the weak/little beat (microbeat)

- Musical interpretation, the first eighth note will be played with more emphasis since it appears on the macrobeat.

- Since I used the syllable “Di” we know we’re in triple meter (Beat function syllables in triple meter are: Du Da Di)

- You also know that the first eighth note appears on the microbeat beat in triple meter (what we would refer to in numerical counting as beat 3), the second eighth note is played on the division of the microbeat, and the quarter note is played on the macrobeat.

- Interpreting that pattern musically, we know that the quarter note will be played with more emphasis than the 8th notes, since it’s on the strong/macrobeat.

By using a numerical (arithmetic) counting system we really don’t get this same information, unless it’s all outlined as I have done with the bullets, so there is a lot of explaining that has to happen with the student when we use the numerical approach. In the first example we would count “1+ 2”. That doesn’t tell us the meter at all, as we have no indication of what comes next, e.g. are there 3 beats in the measure, are there 4, 6, etc? In the second example this will tell me a bit more if I count, “3 + 1”. As then we know, oh, we’re going over a barline because we heard “1”. But lets move this pattern to the beginning of the measure, again if we count “1 + 2”. We really have no idea of any meter, how many beats in a measure and so on. So it’s very inconsistent, whereas, by using rhythm syllables we know exactly what meter we are in, and where we are in the measure in relation to beat function. So it provides loads of information with just three syllables. It provides the syntax of that rhythm pattern.

Here is where the confusion arises in an arithmetic approach to counting. In 4/4 a quarter note gets 1 beat/count. In 2/2 though, a quarter note gets half a beat/count. In 2/8 a quarter note gets two counts. So it changes dependent on the meter. This causes a lot of confusion for students. Whereas, if we count in regard to beat function we are always thinking in regard to macrobeat (the big beat) and the microbeat (the little beat), a more musical approach. As you saw in the article, “Developing the Internal Rhythm within our Students” in the Jan 2015 issue of OPUS, examples of Silent Night using the arithmetic approach to rhythm show there are numerous ways of counting the various meters, which is quite confusing. With beat placement you can count the various meters in the same manner, much easier for students to understand and it makes for a stronger musical interpretation.

Even now, when I teach theory to my students, I’m getting away from the arithmetic approach to rhythm and am basing it on beat function. There is no need to use the arithmetic approach to rhythm, but rather it’s based on macrobeat, microbeat, divisions and elongations. Even in teaching theory where students have to fill in rests or missing beats, this can be done through the understanding of divisions and elongations of the beat. There really isn’t a need to take the arithmetic approach to rhythm, as it’s unstable, because it changes, dependent on the time signature. Rather I take an approach based on what is the macrobeat, what is the microbeat, and deal with enrhythmic values of patterns. Once the macrobeat and microbeat are defined, all else falls into place.

SJC: Is there a point in the training where you make the transition to numerical reasoning?

GC: As mentioned above, no. There isn’t any reason to use numbers with rhythms if using a beat function approach to rhythm. In teaching students theory, I’m amazed how much easier this is for them and they pick it up way faster than when I use to teach rhythm using an arithmetic approach. But again, now I know, this is how the brain learns rhythm, so it’s a more organic approach and is an approach based on how the brain learns and processes rhythm.

SJC: How can teachers guide the students in a way that they fully understand the context instead of simply memorizing and regurgitating the rhythmic syllables?

GC: The secret is start using this from the very beginning, and foremost, the teachers have to change their own thinking. We generally teach the way we were taught, and so it takes some “un-learning” to fully accept this when we’ve all been taught to count using numbers. It’s important for the teacher to fully understand first (as with most things we teach). I approach this first with lots of Aural/Oral associations. We will chant lots of rhythms before students see the notation of these patterns and they will repeat back the rhythm pattern on “bah” or other neutral syllable. As well, at the beginning rhythm patterns, and tonal patterns are taught separately from one another. This way they can concentrate on one thing at a time, again a process of how the brain learns. As we do this, we start building a musical vocabulary for the student, and they have the musical comprehension right from the beginning, of knowing if they are in duple meter, triple meter, the macrobeats, microbeats and so on.

To really give students the context and understanding of rhythm, we use lots of movement. Once they are comfortable with the aural/oral level, then we move to the verbal association level, which is using the rhythm syllables that I mentioned earlier. In both the Aural/Oral and Verbal Association levels, we start with duple meter, and then move to triple meter; and again this is based on how the brain learns and processes rhythm. It’s important to remember that the rhythm syllables do not teach rhythm, (just as a metronome does not help students to play the correct rhythm), rather the rhythm syllables are a tool to help students understand rhythm. That is where to start and then there are a series of sequential levels and activities that follow after this.

SJC: Are there method books or music books for young students in the market that are easily adaptable to your method of teaching rhythm? Do you believe it’s applicable to all music?

GC: There is a piano method series called, “Music Moves for Piano” by Marilyn Lowe. These are published by GIA Publications in Chicago. Here is Marilyn’s website: http://www.musicmovesforpiano.com/

Yes, I do believe this is applicable to all music, and all levels of music. I use this with all my students, even those at the Associate level.

SJC: You suggest similar approaches in your writing, “I don’t teach my students to count, because I want them to feel the beat.” Published in the Fall 2015 issue of OPUS. If you teach the meters and macrobeats/microbeats first to students, how do you propose on making the transition to figuring out rhythms?

GC: Do you mean the rhythmic values of the notes? I guess I’m not sure what you mean by “figuring out rhythms”. First we don’t take a look at individual notes, as that would be similar to only saying one letter at a time when we speak. Rather we take a look at the rhythmic patterns. However, before we begin, we take a look at the Measure signature (time signature) to determine what is the macrobeat and what is the microbeat. Or at the higher levels, we take a look at the context of the passage. Once the macrobeat and microbeat are understood, then we move to the divisions of the macrobeat and microbeat and then to the elongation of the macrobeat and microbeat. It’s part of the sequential process.

SJC: While this may result in more musical growth and understanding, wouldn’t this, in a sense, limit the students’ concepts of “counting” or figuring out rhythms to only the meters they know?

GC: Hmmmmm . . . I would say the opposite. That is what I love about a beat function approach to rhythm, is that it gives more flexibility in understanding the various meters. Where as with an arithmetic approach to counting the student needs to understand the individual rhythmic value of each note. If I say to students we are in duple meter, they know they will be audiating DU DE, or in triple they know they will audiate DU DA DI, and then we have the various rhythm syllables for irregular meters as well. With the arithmetic approach, they have to know whether the quarter note gets 1 count, 2 counts, half a count, two-thirds of a count and so on. So in that sense, the numerical/arithmetic approach is more limiting to only the meters/time signatures that they know.

SJC: I see more and more modern music being incorporated into the repertoire selections of the RCM examinations even for lower levels. If you were to encounter a piece without standard meter, how will you prepare the students to work on that piece within the frames of your usual teaching?

GC: When you mention standard meter, I’m assuming you are referring to duple and triple meter? So with irregular meter, what we (those who base their teaching on the framework of Music Learning Theory, which is the process of how we learn music), we would refer to 5/4, 5/8 etc as Unusual paired meter, and 7/8, 7/4 etc to Unusual Unpaired meter. For unusual paired meter we use the syllables Du Be Du Ba Bi (if grouped 2 and 3), or Du Ba Bi, Du Be (if grouped in 3 and 2). In 7/4, 7/8, etc we would use the syllables, Du Ba Bi Du Be Du Be (if grouped in 3 + 2 + 2), again this would vary according to the groupings. An advantage to this over the numerical accounting to 1 2 3 4 5 or 1 2 3 4 5 6 7, the grouping of the patterns is clearly understood by how it’s counted with the rhythm syllables, which will result in a more musical treatment to rhythm.

SJC: The object to your teaching is to personally adjust and cater to every individual student’s needs. However, just by looking at how you approach rhythms, you seem to have your own firm set of teaching methods. How do you generally balance the specific needs of students to your style of teaching?

GC: Okay, I think this is taken a bit out of context, but I understand what you’re asking. J I think most us do teach to the individual students and to where they are at, one of the beautiful things about teaching private lessons. So in many cases this isn’t new (to teach to the individual differences of the student), but it’s often not mentioned in the teacher’s teaching philosophy. Unlike the school system where the teacher has to teach to the whole class, we get to work with students at the level they are learning. What I mean by that, while Johnny may be at this stage, Susie may be at that stage, and so that guides my instruction. I’m not requiring that all my students learn duple rhythm verbal association this week and they can’t move on until everyone has done this, instead, while one student may be learning duple meter at the aural/oral level, another may be learning it at the verbal association level, while another student may be learning unusual unpaired meter, and so on. What I mean by I teach to the individual differences of the students, is that while one student may be high in rhythm aptitude, but low in tonal aptitude, I work with this accordingly, giving rhythm patterns that are geared to students with high rhythm aptitude and will give tonal patterns that are geared towards those with lower tonal aptitude. So not all students will get the same patterns, nor in the same order, nor learn at the same pace. I follow their guidance and learning level rather than saying that we must get through a unit in the method book every two weeks, or after this piece, lets turn the page and you must do that piece. So the instruction really varies from student to student, but the techniques used in delivering the concepts are pretty much the same. Now I even say that with hesitation because again there are even variances in that, due to the individual student.

SJC: How does this apply to transfer students?

GC: You present a very good question in regard to how it applies to transfer students. This is quite an untraditional approach, although very sound in neuroscience (pardon the pun). So with my transfer students I do carry on with on how they have been taught (symbol/sign before sound). However, I will still work with them at the aural/oral and verbal association levels and work through the sequential process accordingly. So my teaching then becomes compensatory instruction. I use their sight reading and ear training lots to incorporate these new concepts and so that helps to bring them up to where I want them to be overall. It’s a process, and again, that process varies from student to student, depending on where they are at, musically. And I guess that is the key, as I teach to the musical age of the student, not the chronological age of the student.

SJC: You must constantly come across many new things through your research hence discovering the innovative ways to teach rhythm and intervals. What are some difficulties you have as a teacher, mentor, or colleague deriving your own materials away from the popular, common, or traditional methods of teaching?

GC: In regard to “materials” I’m assuming you are talking about physical materials, e.g. books and such? That is the beauty of how I teach, is that it can be used with any kind of music. It’s not indigenous to any one type of music. The framework of Music Learning Theory is used for early childhood music classes, which I teach, any private instrument, elementary music class, high school jazz band, concert band, university music. I guess because this is a framework that I use it’s a matter of adapting it to what I’m teaching. I guess the biggest challenge is finding the time to find the materials to use in incorporating this framework for the specific learning level of each student. So it does mean pulling from various resources if I’m not using the Music Moves for Piano method series. The beauty of this framework is that it can be used with the popular, common, or traditional method books, I just approach the learning of these pieces differently than what is stated. Now I’m selective in what pieces I use with my students, and I often do change them, according to learning level of the student, so it does require a fair bit of digging and prep work.

SJC: Do you feel that teachers should constantly strive to adjust and adapt their teaching in correspondence to newer researches in early education?

GC: Yes, providing it’s proper research. With advances we have in neuroscience we are now able to learn so much more about how our brain learns and processes information. We are finding that often times the traditional way is counterproductive to how we really learn. It’s really only been in the last 15 years where neuroscience has really taken off, with the use of MRIs, CT scans, and so on. And there is still so much we don’t know about the brain and how it works, we’re still very much in the infancy stage of this whole process.

SJC: Is it safe to assume that your teaching focuses heavily on the psychology of the students?

GC: If we are speaking of the psychology of how students learn, then yes, that is a safe assumption to make. J I think the key point to establishing an individualized teaching approach is that one has to understand how we learn and process music. So we need to understand that whole learning process, and this is huge and why I decided to do my masters degree in Music Learning Theory.

SJC: What are some key points to address when establishing individualized teaching methods to any given student?

GC: I think it’s important to realize that each student is at a different musical age. And that is especially true in the birth to 6 year of age. However, we may still get someone who comes to us at age 7 for piano lessons, but they are really at the infant musical age level (acculturation stage), and meanwhile we may get a student who is 5 years of age and has already entered the audiation stages of learning. So by doing various informal activities a person is able to assess their musical age and then you work on from there. The other thing to remember is that although they may be at one stage rhythmically, they may be at a different learning stage tonally, and even at a different learning stage harmonically. However, once the student’s music aptitude has been tested, then of course that gives a more objective approach to the teaching and brings it to another level of individualized instruction.

SJC: You mentioned that learning music is like learning a language. What are some common reverse psychologies that music teachers practice in their teaching?

GC: Well the most common reverse psychologies that music teachers, who use a traditional approach, would be the equivalent of saying to a child that you cannot speak a word until you can read the word. J We know that is crazy, and would say that is crazy thinking, but yet we do it with music all the time - sight/symbol before sound. At least I know I was guilty of doing that for 30 years of teaching. As I mentioned earlier, we usually teach the way we were taught and most of us have been taught to read/decode first. And we miss the most important stage, and that is the stage of listening to music.

SJC: History has shaped teaching music that way it is for decades – so why the change now?

GC: Believe it or not, this is how music was originally taught, way back when. I’m speaking back in Bach’s time. It wasn’t until Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press that this approach changed. Up until that time, music was taught as an “aural” art, rather than a “visual” art. So in many ways it’s not changing but rather going back, or rather, thinking that all things move in a cyclical manner, that we are now returning to the origin of how music was taught, and that is, aurally.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed